Does it matter?

Marching for humanity in Gaza. Sydney Harbour Bridge, August 2025 ©Matthew Smeal

My recent images from Sydney’s march for Gaza had me receive some very nice comments across various social media platforms and in person. One comment from an old friend was a simple question, one word and a question mark: ‘Camera?’

I was ready to launch into the usual response of it doesn’t matter, the best camera is the one you have with you, it’s not the camera it’s the photographer, no one asks a builder which brand of hammer they use, and all that—and I even toyed with replying with ‘Yes, you’re right, I used a camera’.

I soon climbed off my high-horse and replied with a simple ‘Nikon D750 and prime lenses’, taking some joy and vindication in announcing that the photos everyone were moved by were taken with a camera released in 2014.

But I’ve been pondering the question for a week now: What does it matter? Or perhaps, Why does it matter?

It was an honest question which deserved an honest answer. It was from someone with a genuine interest in photography who just wanted to know what gear I used. And admittedly, I nerd out with the best of them; spending far too much time on YouTube and googling bags and cameras and lenses and trying to see who uses what. Why? Because I have a genuine interest in photography – just like my friend.

But researching camera gear, watching infinite YouTube reviews, reading comments and questions from amateur photographers does upset me – because the focus is skewed so heavily towards camera features, it is rarely on art or ability.

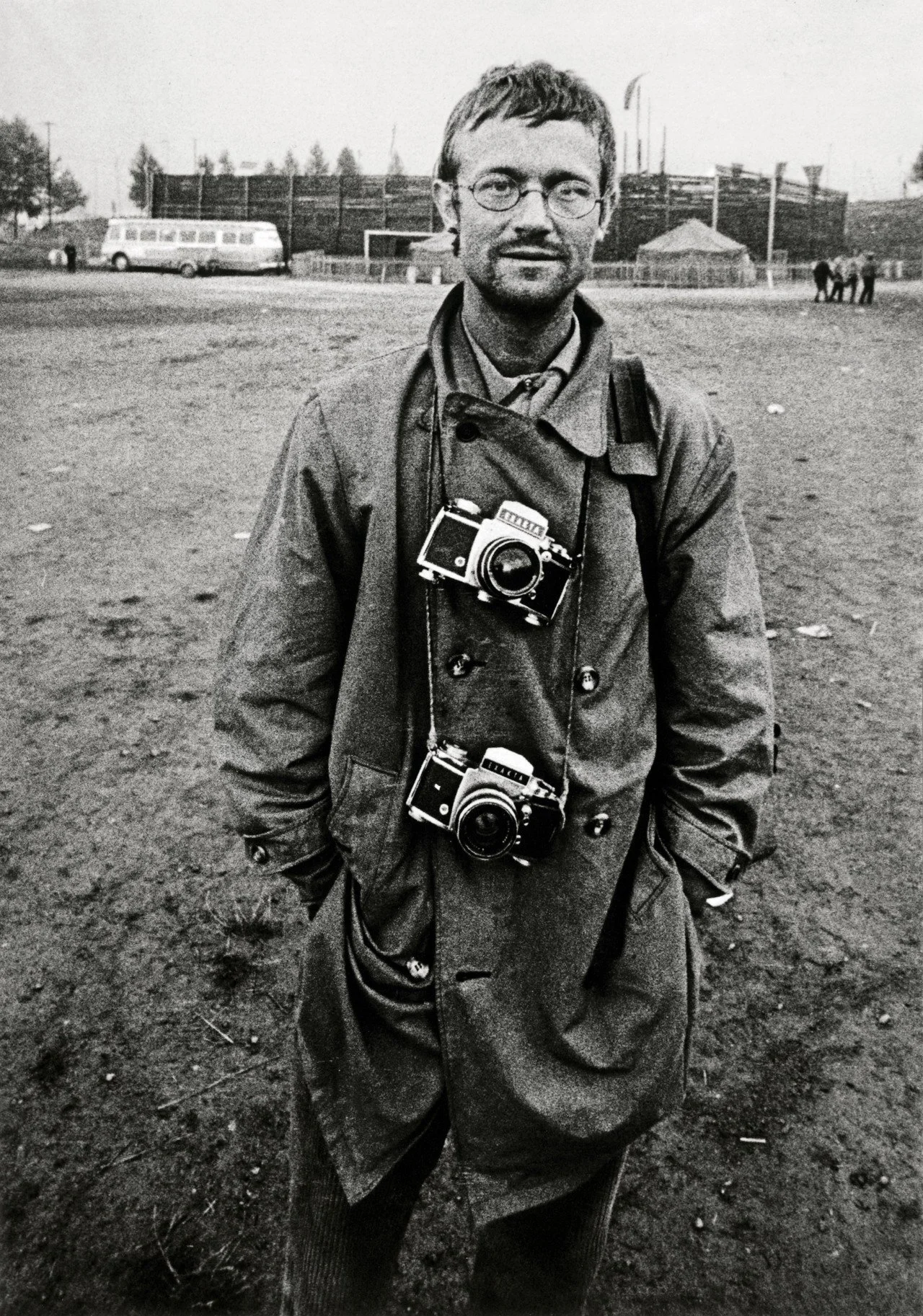

Above: Josef Koudelka with two Exakta cameras, Slovakia 1968.

Reviewers leave scathing reviews on autofocus systems only having 21 focus points not 51; that the continuous motion tracking is rubbish; that it only shoots 4K video, not 8K; that the sensor is a meagre 24 megapixels not 50 or 60; that 100 fps burst rates aren’t enough...and on it goes.

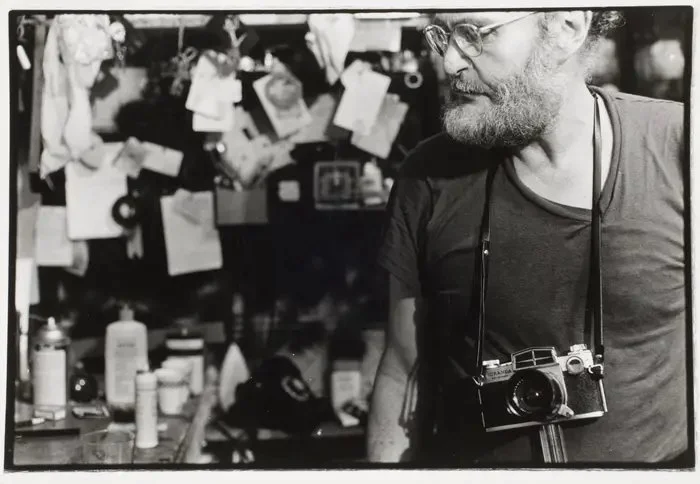

Then I consider the great photographers. Don McCullin shot his incredible Vietnam work with a Nikon F and either a 28mm or 135mm. Steve McCurry shot his uber-famous Afghan Girl portrait on a Nikon FM2 and a 105. Galen Rowell once wrote, ‘Ninety percent of my best life's work could have been made with a manual body, a 24mm lens, and a telephoto zoom in the 80-200mm range.’ Henri Cartier-Bresson mostly used a 50mm lens on the front of his Leica. Diane Arbus used a twin lens reflex (TLR) Mamiya C220 for her street work; Vivian Maier used a Rollieflex TLR. Josef Koudelka used cheap Exakta cameras and favoured a 25mm lens for much of his early work; and one of the greatest documentary photographers of all time, W. Eugene Smith, who was often in financial difficulty, was known for using anything at hand until Minolta helped him out.

Above: W. Eugene Smith with a Miranda Sensorex camera

I’m not sensing much about camera features in the above – or autofocus; but I do sense simplicity. And while these cameras were often at the top of the game during their day, there were, by today’s standards, incredibly basic.

Above: Diane Arbus with her Mamiya C220

When I am up on my high-horse, I like to say that a camera needs three ‘features’: it needs light through a lens (aperture), it needs a way to adjust the amount of time that light is recorded (shutter speed) and the photographer needs to focus the lens. Aperture, shutter speed and focus. With digital cameras you can add ISO but that was an external consideration with film.

My most recent camera purchase was a Nikon Df. It was a camera that came out in 2013, before the D750. I bought it because a) I’d always wanted one; b) because it’s the closest digital camera I can find that gives me a Nikon film camera feel; and c) the image quality is stunning.

Above: A rather nice purchase! Nikon Df

The Df got largely panned when it was released for some of the reasons I mentioned earlier: a slower autofocus system borrowed from the D600/610, no video, one card slot, it only had a 16-megapixel sensor and not the newer 24-megapixel sensor... but many loved it and still do. Those who shot manual focus lenses didn’t care about the autofocus system; those who didn’t see a DSLR having anything to do with video didn’t need video anyway; those who were used to having one roll of film in their camera at a time, didn’t care that it only had one card slot. An ISO dial and not a menu was actually preferred; so too was the shutter speed dial and the ability to use Nikon’s legacy lenses including their non-AI ones.

The modern features were there if you wanted them, vis-à-vis the much-maligned lower end autofocus, but that’s not why the camera was developed. It was designed for simplicity, for giving something to photographers who cut their teeth on manual focus lenses and film; to allow photographers to get on with the task of taking photos without getting caught up in pixel peeping and menu diving.

Above: Henri Cartier-Bresson. Just a man with a small camera and one lens, keeping it simple – while taking images that revolutionised photography.

Simplicity isn’t limiting, it’s freeing. Work with what you have. Learn to shoot with one or two lenses only; try zone focussing; Sunny 16 your exposure; favour one f/stop or one shutter speed for your style; pick one colour profile, tweak it if needed to suit your vision, save it as your standard and stick with it.

It’s fun to nerd out and fall down YouTube rabbit holes looking at the latest and greatest gear. But whenever I start thinking my gear is inadequate, that I need to upgrade, that more lenses would be better, I think of photographers like Josef Koudelka, who carried two cameras and two lenses and a backpack full of film; who slept on the ground in a sleeping bag for years, and went months before being able to develop exposed film; who kept his life simple so he could simply document the world around him.

Does it matter what we use? No, of course not. What matters is we do it.