Edward Colston – What’s in a name

Edward Colston: Philanthropist, merchant, slave trader. This statue in Bristol was pulled down and thrown into Bristol Harbour during the Black Lives Matter protest in June 2020.

My full name is Matthew Colston Smeal. Colston is an interesting name and it’s one that is in the news today as Black Lives Matter protestors in Britain toppled the statue of Edward Colston and threw it into Bristol harbour.

Edward Colston was a leading philanthropist and very successful merchant from Bristol in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Colston paid for schools, hospitals, housing for the poor – many of his charitable foundations are apparently still in existence today. There are streets, schools, a concert hall, and even a sweet bun named after him. But Edward Colston has been a polemic figure in British and Bristolian history for some time. His wealth and subsequent philanthropy came at a cost – a human one. Colston was a slave trader.

During the 1680s, it is believed that Colston’s company, the Royal Africa Company, to which Colston rose to the most senior executive position, transported as many as 100,000 men, women and children as slaves from West Africa to America and the Caribbean – even branding them with the initials RAC.

My maternal family is from Bristol. My grandfather’s first name was Colston. His sister’s middle name was Colston. My great-grandfather had it as a middle name. I believe it goes a fair way back. The name was passed on to me and I, happy to continue the family tradition, passed on the name to my own son.

But I’d never heard of Edward Colston. All I knew was Colston was a prominent Bristol name and a name that had been part of my mother’s family for generations.

Several years ago I got to know some people from Bristol. I would see them each time they visited Australia, which was frequent because of their own Bristol–Australia family connection. Outside of that we had occasional email and social media contact. As I was chatting to them during one of their visits, I mentioned my middle name and family connection to their city. They looked at me aghast. “You should probably keep that quiet,” they said, “and if you ever come to Bristol, seriously, just don’t tell anyone.” What had been friendly and warm very quickly became weird. I was confused and clearly ignorant. “Colston isn’t a name anyone wants to be associated with,” they said. They briefly explained why.

I was horrified and went home and straight to Google. Within minutes I was ashamed of the unique name I had been quite fond of all my life but was more ashamed and disturbed that I had so ignorantly passed on the name of a slave trader to my son.

Now while I don’t believe we are actually related to Edward Colston—and I don’t want to look too closely—carrying and continuing a name that personifies all that I oppose, is distressing. So is watching a rapturous crowd throwing a statue of your namesake into a harbour. I only wish I’d looked further into the name before passing it to my son.

But I found some balance.

Several years ago, and perhaps sparked a little by the above, I started doing what everyone in their mid-to-late 40s seems to do and began researching my family history. But instead of looking further into my mother’s side, I wanted to know about the Smeal name of which I knew nothing. I barely knew my paternal grandparents, uncle and cousins, my father passed away when I was in my early 20s and never mentioned our name or family history – not that I cared at that time anyway.

Smeals, as I’d always hoped and suspected, are from Scotland. Many Smeal families stretch from Edinburgh across Midlothian and West Lothian towards Glasgow. And there were some very notable Smeals in Scottish history – notable because of their leadership and promotion of one particular issue: the abolition of slavery.

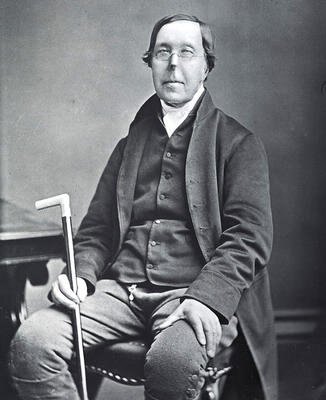

William Smeal founded the Glasgow Anti-Slavery Society, which later became the Glasgow Emancipation Society, and he attended the first World Anti-Slavery Convention that was held in London in 1840.

Above: Quaker and abolitionist William Smeal

William Smeal’s family is interesting in itself because they were Quakers – interesting because there were believed to be only around 400 Quakers in Scotland at the time. As Quakers they held strong beliefs about social injustice. Apart from being an abolitionist, William’s campaigning and social interests included a repeal of the ‘Corn Laws’—laws that placed huge tariffs on the importation of corn, oats, barley and wheat, which protected wealthy landowners but created high prices for such staple foods at a time when many poorer British citizens were starving—the consumption of alcohol, capital punishment and war.

But it is Jane Smeal, William’s younger sister that is truly fascinating. Like her brother, Jane Smeal was a Quaker, an abolitionist and, where William founded the Glasgow Emancipation Society, Jane became leader of the Glasgow Ladies Emancipation Society. In 1838 Jane, with fellow abolitionist Elizabeth Pease, published the Address to the Women of Great Britain, a call for women to speak out against slavery and to form their own abolitionist societies. Smeal also prepared an address for Queen Victoria that has been credited as the final push that ended slavery in the Caribbean.

Above: Jane Smeal (right) with other abolitionists and women’s suffrage activists – her stepdaughter Eliza Wigham (left) and Mary Estlin (middle).

Jane Smeal married John Wigham, another Quaker and abolitionist who had lost his wife and two of his children but whose daughter Eliza was still alive. Jane became close with Eliza and the stepmother/stepdaughter duo continued their abolitionist activities. Their work soon incorporated the promotion of women’s rights and the pair established the Edinburgh chapter of the National Society of Women's Suffrage.

In recent years, Jane Smeal, Eliza Wigham, Elizabeth Pease and fellow Quaker, abolitionist and women’s suffrage activist Priscilla Bright McLaren, became the focus of ‘Edinburgh’s Forgotten Heroines’, a campaign to raise awareness about the women’s efforts to abolish slavery and create equality for women in Scotland and Great Britain.

My guess is that no one would want to pull down a statue dedicated to them.