Legacy of a deeper vision – studying the masters

‘The Last Rose’, a still life by Josef Sudek

A new photography book – Josef Sudek: Legacy of a Deeper Vision – arrived the other day.

It was perfect timing because I had just lent some of my other new books—by Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and Ruth Bernhard—to a friend. I had photographed her a week earlier, the shoot going so well and both of us being so comfortable, that we began discussing a new project – nudes. The books were by three of photography’s great photographers of the nude and I wanted my friend to find poses and ideas she liked, while seeing the beautiful work of those who had come before. Books were certainly safer than googling ‘nude photography’.

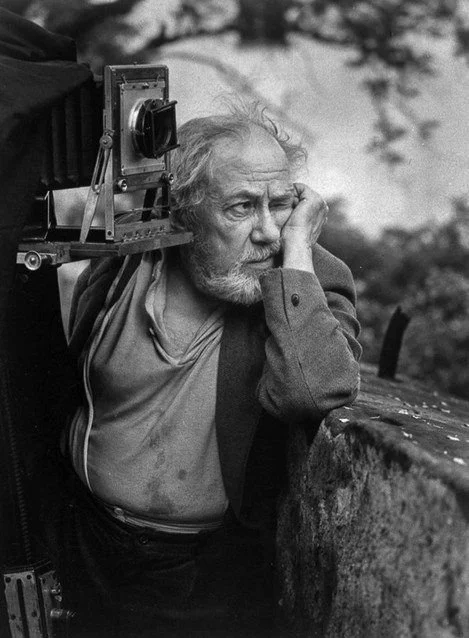

Josef Sudek – ‘the poet of Prague’

It gave me time to be alone with Sudek’s book and its 175 plates and several essays. The book follows me everywhere: by my bed, on the coffee table, in my study… Whenever I find time, I sit quietly and absorb more work by this incredible artist. His use of light, shadow, texture; there is a softness and a warmth that is mesmerising. I am yet to read the essays, I want to leave his work unadulterated by other views for now and enjoy the quiet study of contemplation.

Years ago I established quite a photography book collection: Edward Weston (a few), Ansel Adams (many), Brett Weston, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Sebastiao Salgado, Edward Curtis, several biographies and narratives; and the first photography book I ever bought: a 40-year retrospective by Jeanloup Sieff. I still remember standing in Dymocks bookshop in the centre of Sydney in the early 1990s, having flipped through the book on previous visits, and returning with $69 which was a lot then – and now still – and surprising given I was a poor cinematography student at the time. But photography was where my heart was and my mind was being blown by the work of the photographers I was discovering. It was a book I have come back to time and again, Sieff’s images and captions and his cheeky wit evident in both, becoming remarkably familiar.

Books were how we learned back then; the internet was in its infancy, digital cameras still more than a decade away and browsing the art and photography section of major booksellers was where I learned the now-familiar names: Weston (all of them: Edward, Brett, Cole), Adams, Cunningham, Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand, Group f/64, Cartier-Bresson, Capa, McCullin, Salgado, McCurry, Brandt, Sieff...

Cole Weston’s colour work was a break away from his father and brother, but he knew from his father that ‘composition is the strongest way of seeing’.

The internet changed information gathering enormously – and provided a broadcast platform for anybody. Within a short space of time, the true masters of the art and craft of photography, and good documentaries about great work, ran counter to anyone with a prominent YouTube channel. Photography information became about new gear, not new work or the enduring work of the greats – and in the burgeoning world of digital cameras with more features, more megapixels, more autofocus points, better video capability, it’s easy to forgive the excitement. But the digital age also ushered in a sense of impatience: the speed of upgrades and updates forcing the continual superseding of what was cutting edge only a year before.

The film and brands of old changed too: Agfa disappeared, Kodak did too but came back much smaller and more niche; Minolta, which had already merged with Konica, was swallowed by Sony; and Ilford was taken over by Haman. And bookshops were closing. The change was rapid and the excitement was in the technology.

Imogen Cunningham, Three Dancers, Mills College, 1930. No autofocus, no focus tracking, no high speed shutter, no motor drive, no matrix metering, no…

To apply Marshall McLuhan’s theory that ‘the medium is the message’, we could argue that for many photographers, the medium of photography has become less about its storytelling or artistic ability, and more about its technology – that the focus is far more devoted to ‘pixel peeping’ and not on the art. ‘What camera did you use?’ is a question I am asked often by other photographers. It is never, ‘What were you thinking at the time?’

Idly searching for photography business information, I chanced upon a post asking what photographers would do differently if they were starting their business today. One replied that they would spend far less time looking at YouTube photographers—who benefit from having gear sent to them for review and purchases made through affiliate links—and much more time studying the work of great photographers.

Minor White brought a spirituality to his work that reflected his deeper vision, personality and creativity.

The post gave me pause. I often spend way too much time seeking validation online. But I was also reminded of the book purchases I have made in the past year or two: the new Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham and Ruth Bernhard books mentioned earlier, now sit alongside those of Josef Koudelka, Lee Miller, Bruce Barnbaum, Vivien Maier, Lucien Clergue, Susan Sontag, Minor White, Robert Doisneau, Henri Cartier-Bresson, David Douglas Duncan, Sally Mann, and now, Josef Sudek. I enjoy those books immensely: spending quiet moments slowly turning the pages, absorbing each image’s framing, composition, light, texture...

Most YouTube channels are simply marketing: creating a perceived need. Your camera is too old. Your camera only has 24 megapixels and 21 autofocus points. Your lens does not have stabilisation. Why you need to upgrade to this camera. Ten tricks the pros use. Five tips to make your photography pop. How to level up your photography…

Josef Koudelka, a simple life and a photographic legacy that will inspire generations.

When you study the work of the masters, you realise that they didn’t have those modern ‘advancements’ either. Many used cumbersome view cameras; many used simple Leica’s, Nikon’s, Minolta’s..., Koudelka travelled the world with two Leica’s, two lenses and a bag of film; sleeping on floors, in fields, and eating simply, processing months’ worth of film whenever he got a chance. His earlier work of the 1968 invasion of Prague that brought him to the world’s attention, was shot on two rudimentary Exakta cameras. The Nikon F’s legacy from the Vietnam War era is legendary: no meter, no autofocus, no zooms – and a top shutter speed of 1/1000 sec. Henri Cartier-Bresson is known to have carried one camera, one lens (a 50mm) and preferred a shutter speed of 1/125. ISO was determined by the film, not an automatic feature; pushing and pulling in development if adjustment was needed. Sieff shot mostly with a 28mm lens. Don McCullin did too, with a 135 for the long stuff. Vivian Maier used a twin-lens Rolleiflex. Sudek lost an arm in the First World War yet still managed to lug a view camera around the streets of Prague, loading film holders and developing and printing an exquisite body of work. Everything mentioned above were prime lenses requiring manual focus.

‘Still life with milk and fruit’. My own foray into still life inspired by Sudek, and perhaps by Cezanne. © Matthew Smeal 2026.

I’ve never had a client ask me what camera I use – stills or video. Unless they are an enthusiast, it means nothing. I have recently begun shooting a lot of portraits; whenever I mention I’ll shoot some on digital, some on 35mm and some on 120, I get blank stares. Brands like Mamiya mean nothing to the person in front of my lens. They don’t care if I’m shooting FP4, HP5, Tri-X, Fomapan... or whether my camera has 16, 24 or 50 megapixels...or whether I’m developing in Rodinal or Ilfotec HC or ID-11, or what brand of SD card I use. While my medium format gear can be an interesting conversation topic that helps break the ice while setting up – simply because it is unusual – the model honestly doesn’t care. Neither does the flower, the tree, the rock, the ocean…

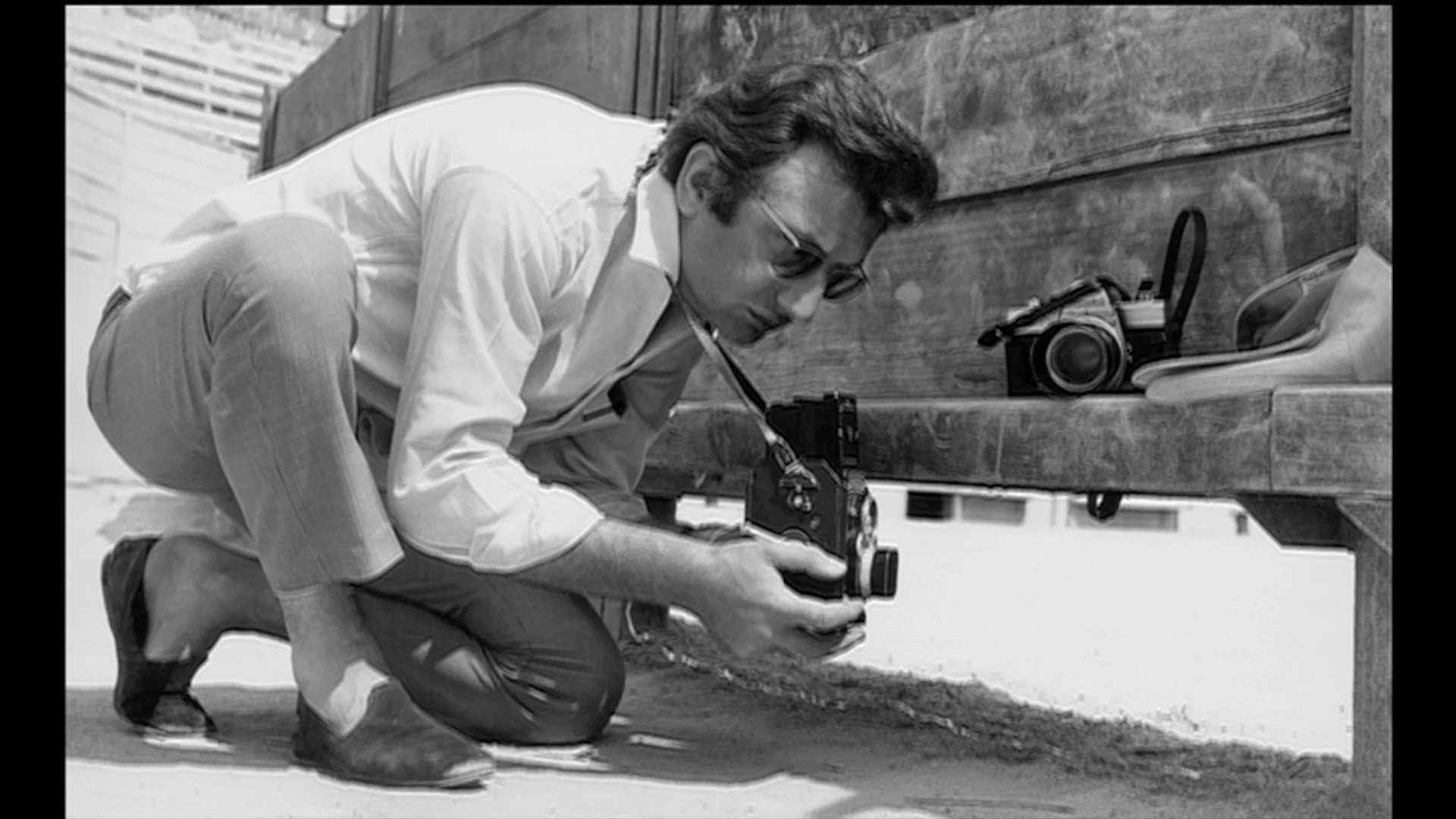

Lucien Clergue – a Rolleiflex for the larger 6×6 negative and to get down low, and a Minolta for everything else.

Lucien Clergue spent his time studying sculpture in the galleries of France: the proportions from head to breast to waist to feet; the way the light fell, the poses they were crafted in. Cartier-Bresson was also an illustrator. Ansel Adams was a classical pianist before he became a photographer. Ruth Bernhard was influenced by her father, an internationally renowned graphic artist. Steiglitz married the great modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe, and it’s fair to say they influenced each other. Lee Miller’s father was an adventurous amateur photographer, and she was a leading model before stepping behind the camera and becoming an assistant and muse to Man Ray and friend to Picasso.

Their cameras were their tools, their inspiration came from galleries, light, nature, music, each other. We live in a time when technological advancements in photography are mirrored by an insatiable appetite for internet content. Fast developing technology is nothing new, but it’s worth remembering that running parallel to technology is the simplicity of someone wandering the rocks and dunes of California with an 8x10 view camera; a lone man in Paris with a 50mm lens; a nanny on the streets of Chicago and New York with a Rolleiflex around her neck and children in tow; and a one-armed veteran struggling through Prague making poetry with a lens.